What is it?

Acne vulgaris is a disease characterized by skin eruptions such as whiteheads, blackheads, pustules, papules, and cysts. Acne can have either noninflammatory or inflammatory lesions or a mixture.

What causes acne?

Acne can be caused by bacterial colonization, increased sebum production, and the abnormal keratinization (changing) of the sebaceous (oil) canals. Acne affects 95% of boys and 83% of girls at the age of 16 but can also occur in the adult population.1 It is more persistent in females and commonly located on the face. However, males experience more severe forms, with eruptions mainly on the chest and back.

Cutibacterium Acnes, a slow-growing bacterium, most likely causes the infectious nature of acne.

What are the mechanisms of acne?

The modern Western diet is one reason acne is so prevalent in the Western modernized world. One study found that almost zero acne existed in the Kitavan Islanders of Papua New Guinea and the Aché hunter-gatherers of Paraguay.

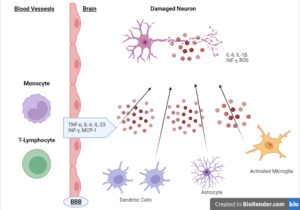

When the sebaceous glands in the skin become sensitive to androgens, it increases the sebum, which is the skin’s oil within the gland. This causes hyperkeritization of the hair follicles, leading to further build-up and inflammation. This inflammation, combined with C Acnes, increases within the sebaceous space and leads to an influx of neutrophils, causing additional inflammation.

Increased androgens are one of the fundamental mechanisms at play. To control acne, these androgens must be addressed.

What are the solutions?

Diet. Diet plays an integral role in acne accumulation, and the mention of androgens suggests an approach that can have a positive effect. Insulin and the ability to increase androgens appear to play a large role in acne, and those who have acne have a much higher prevalence of insulin resistance than those who do not.2

Using a low-glycemic diet with whole, natural foods would be my first step in controlling acne. Dairy has also been shown in observational studies to correlate with increased acne prevalence. Because it’s an observational study, it does not clarify whether it is a cause, but it is still worth consideration when creating a plan. Dosage: Whole foods and low glycemic diets, with potentially the removal of dairy.

Training. Although I couldn’t find studies on training modalities for treating acne, it makes sense that different types of exercise would benefit its reduction. Stress is a key modulator of acne, and modalities to lower stress may be beneficial in lowering the prevalence of acne. Dosage: Modalities to reduce stress can play a role in controlling acne. These modalities include yoga, meditation, and aerobic conditioning.

Lifestyle. When we examine lifestyle and acne, one of the components mentioned constantly in the research is the effects of stress on the presentation of acne. Recently, studies have indicated the mechanism behind the impact of stress.

Observational studies showed a lag time of about two days until acne presentation after the stressful event.3 CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone) released from the brain or locally in the skin can exacerbate skin inflammation and immune responses, leading to increased acne presentation. Dosage: Finding ways to lower stress levels can be of the utmost importance to the remission and avoidance of acne, especially in female populations. Using methods to control the stress axis can be a major lifestyle consideration in acne control.

Supplements

Zinc. Zinc has been shown to affect acne positively, primarily when combined with other nutrients.4 Some studies suggest its efficacy when used in isolation; however, I use it with the nutrients mentioned below. Dosage: Take 15-30mg of zinc daily, in divided doses, with food.

Lactoferrin. Lactoferrin is primarily found in the breast milk of mammals. It has been shown to positively affect acne, presenting a possible role for the gut microbiome in acne control. One study showed that using lactoferrin, vitamin E, and zinc led to marked improvements in acne in children and young adults. Dosage: Take 500mg of lactoferrin in divided doses, away from food.

Vitamin A. Vitamin A has been used successfully in very high doses to treat acne. Although I don’t recommend this approach, using it with other supplements mentioned has been shown to affect acne positively. However, a small study showed that even a lower dose of oral vitamin A could benefit acne vulgaris. Dosage: Based on that study, 20mg of Vitamin A per day can benefit acne. Using cod liver oil with vitamin A could also be beneficial.

Berberine. Berberine has been shown to lower insulin resistance and decrease triglycerides, which are markers of increased acne. It also has other positive effects, especially in women with PCOS, and helps lower androgens, which are also responsible for increased acne.5 Dosage: Take 250mg x 2 daily, with higher-carb meals.

NAC. N-acetyl cysteine is beneficial for its antioxidant properties and ability to increase glutathione. It is also an antimicrobial agent against certain bacteria within the gut and has been shown in a meta-analysis to be a potent modulator of acne.6 Dosage: Take 250-500mg of berberine with your big meals.

Probiotics. Again, it is not a direct influencer of the skin but indicates the effect of the gut microbiome and the gut-skin axis. Probiotics can positively affect acne presentation and total acne.7 They are effective both topically and orally. Dosage: Using different strains of probiotics is the most effective. Using strains of S boulardii and spore-based may be of benefit here. Topical Lactoporin was even shown to reduce acne and fine lines.8

Conclusion

To positively affect acne in a client, take a holistic approach that involves restricting the use of high-glycemic, processed foods. Eliminating dairy from the diet may also be beneficial.

Incorporating a supplement blend seems more beneficial than using any products in isolation. Stress-reducing strategies can also be beneficial to prevent outbreaks.

Reference Links :

1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8953587/

3. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/272775

4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29193602/

5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8538182/

6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33629414/